Periodization: Running with a Purpose

By Matt Marrie, PT, DPT

June 26, 2020

Matt Marrie is currently a resident in the Drexel University

Orthopaedic Physical Therapy Residency Program.

Have you ever wondered why elite runners can log over 50 miles per week without developing an injury? Do you struggle with a nagging injury that prevents you from running as often as you prefer? Is there a way to prevent an injury from happening in the first place? We are here to tell you there is a quick and easy way (also free of cost!) to modify your training program to help prevent injuries.

There is no question that running-related injuries (RRIs) are multifactorial and stem from a myriad of factors that are either intrinsic or extrinsic in nature (1,2,3). Extrinsic refers to the factors that you can control, such as your running form, the shoes you run in, and your training program (2). Intrinsic factors include things such as your age, anatomy, and previous history of injury, things you can’t control (3). Many injured runners seek feedback on their running mechanics or hobble down to their primary care physician for advice. However, many recreational runners fail to identify potential issues with their training program. This is not to say that training programs are more important than the way you run, but they can be changed a lot more easily. The purpose of this blog post is to elaborate on training errors and introduce the idea of periodization, which is a strategy you can implement to prevent injuries. We hope you can walk away from this post with a better understanding of why periodization is important and how you can run with a purpose to avoid injury!

There is a common misconception in recreational runners’ perception of elite runners. Many people think these elite athletes train all year, but they don’t. Elite athletes train a majority of the year, but their programs are structured to include phases of training and recovery, including rest days and periods of no running. The phases of their training programs consist of preparation, competition, and transition. This is the idea of “Periodization”, which is a training strategy that allows for maximal effort while avoiding overtraining (4,5). Overtraining occurs when the human anatomy cannot meet the demand of the stresses it encounters. In most runners this occurs by increasing volume too quickly (weekly mileage) or by training too frequently without allowing the body to recover. The goal of periodization is to build mileage in a progressive manner but also ensuring adequate time for recovery. Let’s break down this idea of periodization:

1. Base endurance: This is what you will need to run in the first place. Aerobic endurance is different for every single person, but generally speaking you should be able to comfortably jog at least one mile without stopping. This can be built up with any mode of aerobic exercise, such as: running, cycling, swimming, walking, ergometers, etc. Usually a combination of training is best.

2. Preparation Phase: This phase is all about building your aerobic capacity and slowly increasing your mileage. This phase mainly consists of runs that challenge endurance but also addresses speed and strength. There are many different programs out there for this phase, such as Couch to 5k. Most of these programs focus on building you to competition phase. Plenty of running experts recommend restricting your mileage progressions to 10% per week (6).

3. Competition Phase: This phase is all about speed. This phase is typically characterized by a reduction in weekly mileage with a simultaneous increase in training intensity. The focus on this phase is finishing runs as fast as possible. This may be in preparation for a specific race, but it can also be used as a personal challenge. If training for a competitive event, it’s also essential to include a taper phase, which consists of reductions in mileage or intensity about 1-2 weeks prior to the event (7). The length of the taper phase is usually dependent on the length of the upcoming competition, with longer races requiring a longer taper phase. This ensures the body is adequately recovered from training and ready to be pushed to the limit.

4. Transition/Recovery Phase: This is arguably the one that us runners tend to forget about and is equally as important as the other phases. This is where you let your body recover and rebuild itself. Detraining does occur, but literature shows that significant metabolic effects do not occur before 7-14 days from stopping activity (8). In other words, you’ll barely notice the changes of a week or two away from running. Additionally, there are plenty of other forms of exercise that you can use to get your heart rate up while sparing your legs. This phase is a great chance to jump into the swimming pool, take gravity out of the picture, and still get a great cardiovascular workout. Cycling and weight training are also other great options during the recovery phase.

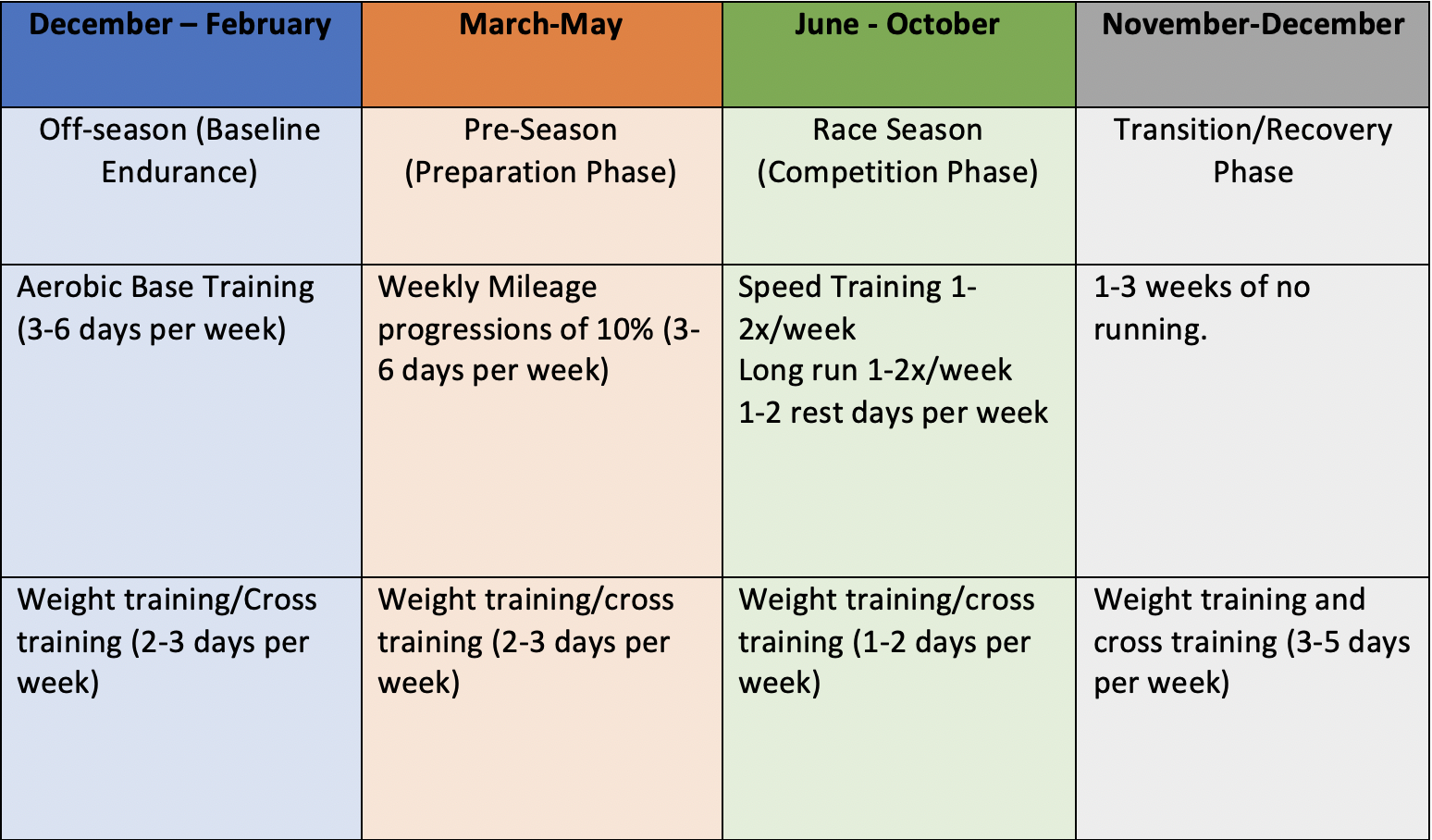

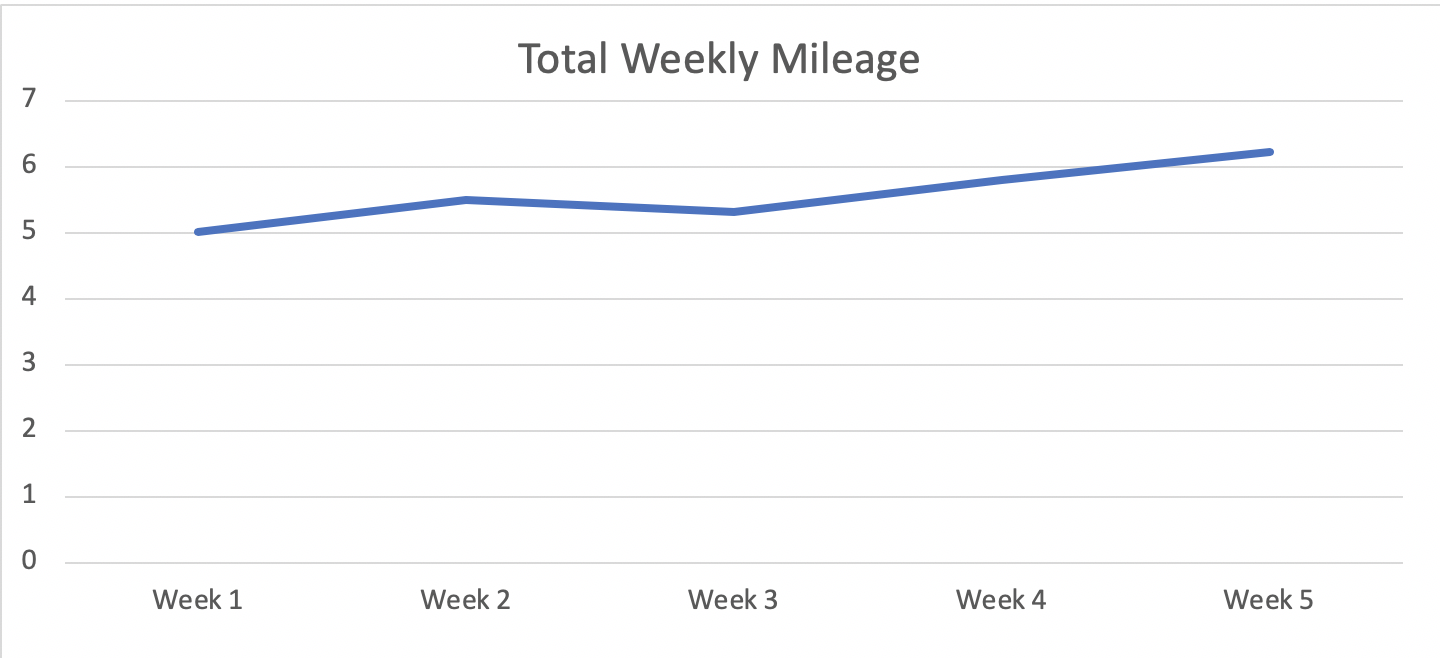

Periodization is important not just for competition, but also injury prevention. You do not have to run in races to use this training idea! If you are a runner, you do it for a reason. Whether it be for fun, brain health, heart health, weight loss, whatever your specific reason is. Periodization is a great place to start to make sure you are training appropriately to avoid injuries that will prevent you from reaching your goals. Running with a purpose can prevent overtraining, allow you to measure progress (such as tracking mileage or even times), and give you a sense of achievement. I have included a sample periodization program below. It is meant to serve as a very basic example of what a typical year-long running program looks like. I have also included an example of a 5-week mileage progression and a 1-week competition phase run schedule.

Figure 1: Skeleton example of basic periodization program. You can visualize the 4 basic phases of periodization broken into Off-season (base training phase), Pre-season (preparation phase), Race Season (Competition phase), and Transition Phase (recovery phase). This chart provides a basic example of the periodization general principles to help you apply them to your training. When creating a periodization program for yourself, you should consider baseline fitness and your goals as a runner.

Figure 2: Basic example of mileage progression during Preparation phase. Note that the progression of total mileage does not have to be linear and it’s not necessary to add total mileage each week. Include some variability into your training program

Figure 3: Example of running schedule during the Competition phase. This example is based on someone who is currently running ~19.5 miles per week in preparation for a half marathon that is 5 weeks away. This person went on to include a 3-week taper phase, characterized by gradual reduction in mileage to 10 miles per week the week prior to the race.

References:

1. Hespanhol Junior LC, Carvalho ACAD, Pena Costa OP, Lopes AD. Lower limb alignment characteristics are not associated with running injuries in runners: prosp

ective cohort study. European Journal of Sports Science. 2016. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17461391.1195878.

2. Hespanhol Junior LC, Pena Costa LO, Lopes AD. Previous injuries and some training characteristics predict running-related injuries in recreational runners: a prospective cohort study. Journal of Physiotherapy. 2013; 59: 263-269.

3. van Gent RN, Siem D, van Middelkoop M, van Os AG, et al. Incidence and determinants of lower extremity running injuries in long distance runners: a systematic review. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2007; 41: 469-480. Doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.033548.

4. Frankel CC, Kravitz L. Periodization: latest studies and practical applications. IDEA Personal Trainer. 11(1): 15-16.

5. https://www.runnersworld.com/training/a20791975/the-three-phases-of-a-running-program-com/

6. Nielsen RO, Parner ET, Nohr EA, Sorensen H, et al. Excessive progression in weekly running distance and risk of running-related injuries: an association which varies according to type of injury. JOSPT. 2014; 44(10): 739-747

7. https://worldsmarathons.com/article/training-periodization-for-long-distance-runners-a-guide-to-your-new-personal-best

8. Neufer PD. The effect of detraining and reduced training on the physiological adaptations to aerobic exercise training. Sports Medicine. 1989; 8(5): 302-320.

9. Wallman H, Rosania J. An introduction to periodization training for the triathlete. National Strength & Conditioning Association. 2001; 23(5): 55-64.